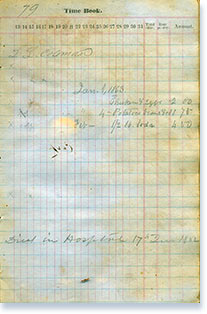

The Civil War Letters of James Harvey Campbell

a collection of thirty-one civil war letters

In this letter James goes into great detail about the rigors of war: long marches to near exhaustion, images of wounded and dead soldiers, lack of food while on march, lack of pay, concerns for his family, and the joys of having a baked chicken for breakfast.

Near Orange C.H. Aug. 14, 1862

My dear wife,

I received your welcome letter yesterday evening and was very glad indeed to hear from you. I have been on the march now almost incessantly ever since I wrote to you before, and am almost broke down. We started from the neighborhood of Gordonsville the day after I wrote to you, and went through Orange into Madison and Culpepper Counties, when we met the Yankees and defeated them and drove them from the battlefield, where we camped that night and the next day and then retired. They left a great many of their dead and wounded on the field where we had a good opportunity of judging of their numbers. Of all the ghastly looking corpses you ever saw, these were the worst. I went all over the battlefield the next morning, and saw scores and hundreds of them lying there sometimes thirty or forty of them lying in a space of nearly as many yards. Sometimes the wounded would be lying close to the dead, and there they laid in the broiling hot sun all the time we were there. I think there must have been at least 500 Yankees killed on the field from what I saw and we took about 400 prisoners and altogether, including the wounded, I think they must have lost some 1500.28 Our loss was probably about 500 in killed and wounded. Our battery was not in the fight, being held in reserve. The victory was complete, considering the numbers engaged. The enemy asked for a flag of truce to bury their dead, which was granted, and we retired from the field. The whole army had now fallen back three miles south of Orange C.H. 13 miles from the field, where we will await, I suppose, until Stonewall gets ready to attack them again. We have had some of the hottest weather up here, I think, I have ever seen, and our men have suffered very much. It is difficult when we are on the march and expecting a fight, to get anything but hard crackers to eat because we cannot keep the wagons along with us and for one and two days we had nothing but those and I thought I should almost starve, but we have got back here to a very pleasant camp, where I hope we will stay at least long enough to recruit our exhausted strength. What do you think I had for breakfast this morning? I had a nice baked chicken. I had to pay 50 cts for it and 10 cts for baking it, but to a hungry and tired man, it was worth it. It tasted better than anything I have eaten since I have been in the army away from home.

My dearest, I am very sorry to hear about Nannie and anxious to hear about yourself. I had hoped you would have been in the country before now, and can only advise you to dispose of Fanny if possible, until I come back. If you do not go soon, it will not be worthwhile to go at all as far as your health is concerned, as the summer is nearly over. We have not got paid off yet, and will not be I suppose, as long as the active campaign continues up here. Should you be compelled to borrow any more funds I think I can be pretty certain to repay very soon. To make sure of you getting this letter, as I don’t know whether it will find you in town, I will enclose it to your brother.

I write this letter on captured paper taken out of a Yankee knapsack which I found on the field. I feel very much concerned about my dear ones at home, and hope, my dearest, you will try to take care of your health. Be sure to kiss the dear children for me. I cannot write more now. I feel very much refreshed today.

From your devoted husband,

J.H. Campbell